For Duke Researchers, Internal Seed Funding Yields a Robust Harvest

Collaboratory grants help faculty grow ideas and build a foundation for larger external grants

When noted autism scholar Geraldine Dawson first came to Duke, she sought to meet a wide range of potential collaborators across campus. At a faculty event one evening, she struck up a conversation with Guillermo Sapiro, the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of Electrical & Computer Engineering. Dawson, the William Cleland Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, soon ended up working with Sapiro on a digital app that is designed to increase the accuracy of autism screening for young children.

Through a Duke Bass Connections team, the pair received a small amount of funding to engage students and other faculty in a year-long project. Dawson and Sapiro subsequently received more substantial financial support from the Office of Information Technology and the Rhodes Information Initiative at Duke. Their multi-year research project eventually resulted in several papers, a collaboration with Apple, a refined app and a $12.5 million grant. They also competed successfully for a $3.9 million grant from NIH to design an infant version of the app, with the goal of detecting autism by 6-9 months of age, before a diagnosis is typically made.

This fall the Duke Center for Autism and Brain Development, which Dawson directs, was awarded an additional $12 million grant to develop AI tools for detecting autism during infancy and identifying biomarkers in the brain.

Collaboratories

Many Duke faculty have leveraged internal seed funding from interdisciplinary units or the Provost’s Office to advance their research and create strong proposals for longer-term external grants. Through the Together Duke academic strategic plan, the university created additional opportunities for faculty to move forward on their big ideas. Established in 2018, the Collaboratories program support groups of faculty whose engaged research targets societal challenges. Here are three examples.

Political Polarization

How can we reimagine social media to reduce partisan conflict about race, religion and citizenship?

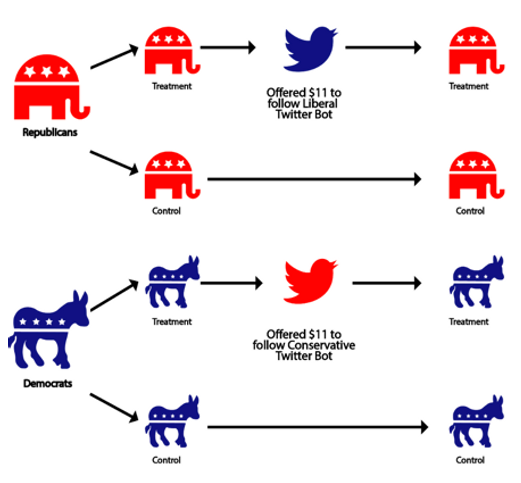

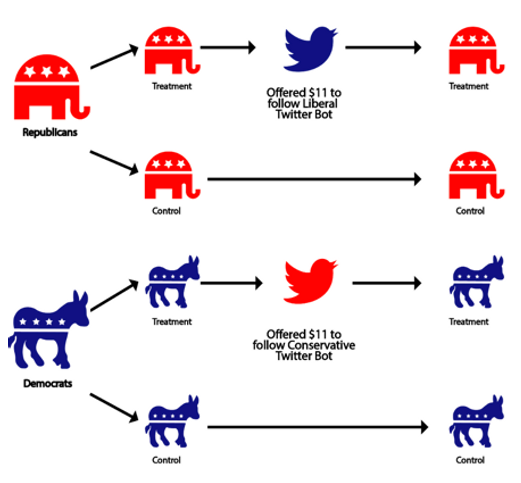

Founded by Christopher Bail, professor of sociology and public policy, The Polarization Lab brings together social scientists, computer scientists and statisticians to study how social media shapes political polarization.

Through one study, the lab’s researchers found that when people are exposed to opposing views on social media, political polarization can actually increase. Building on this research, which was covered by around 40 media organizations, they assessed how Russia’s campaign of social media influence shaped American’s political attitudes and behaviors. The researchers concluded that interacting with the Russian accounts did not have a substantial impact on people.

Through the collaboratory, the lab has expanded into an interdisciplinary community of 28 faculty, graduate students and undergraduates. Members have conducted additional studies and published numerous articles as well as a book (“Breaking the Social Media Prism: How to Make our Platforms Less Polarizing”).

Applying insights from their studies, researchers created tools for social media users to fight political tribalism. In the first month after the tools’ public launch, more than 10,000 people used them. The lab’s work has also influenced social media platforms themselves. Bail’s recommendation for companies to use algorithms that promote posts that gain traction from both Republicans and Democrats, for example, was integral to Twitter’s Community Notes program — a program designed to reduce the spread of misinformation via crowdsourcing.

The lab secured research funding from the National Science Foundation, the Templeton Foundation, the Russell Sage Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, Google, Twitter, and Facebook’s Foundational Integrity Research program.

Moral Artificial Intelligence

How can AI help humans make better judgments about who receives scarce resources?

This collaboratory builds on research through the Moral Attitudes and Decisions Lab and several Bass Connections project teams led by Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, the Chauncey Stillman Professor of Practical Ethics, along with Jana Schaich Borg and Vincent Conitzer. They have been exploring the possibility that artificial intelligence (AI) could serve as a “moral GPS” to help humans make better judgments according to their own standards as well as moral traditions. Researchers draw on computer science, data science, philosophy, economics, game theory, psychology and neuroscience.

Members at Duke and Duke Kunshan universities are comparing American and Chinese moral judgments about uses of AI. The team created culturally appropriate scenarios in various areas — medicine, law, business, education, military and transportation. Researchers gathered and analyzed data about moral judgments of those scenarios from representative samples of Chinese and American survey participants. A follow-up study will test hypotheses about the reasons for the differences the team found.

The collaboratory has produced numerous publications, and a forthcoming book is titled, “Moral Questions About Artificial Intelligence.” Tools for use in experiments include scenarios in English and Chinese; an algorithm for predicting human moral judgments in kidney allocation conflicts; and an online platform for testing consistency with and without AI manipulation.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the team received grants from Oxford University and the World Health Organization to apply their studies to the fair distribution of ventilators and vaccines.

Recently, the group was awarded a $1 million grant from OpenAI to develop algorithms that can predict human moral judgments in scenarios involving conflicts among morally relevant features in medicine, law and business.

Infectious Disease Transmission Pathways

How can we deepen our understanding of what factors turn a local outbreak into a global pandemic?

Led by Charles Nunn, the Gosnell Family Professor in Global Health and professor of evolutionary anthropology, this collaboratory seeks to understand the ecological context of disease transmission between animals and humans. Members conduct research in rural Madagascar, at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore and at Duke University in Durham.

The collaboratory built on a multi-year Bass Connections project that involved students and local partners in Madagascar.

Researchers are collecting and analyzing blood samples from humans and animals, and conducting surveys to gather social network and household data. They will link findings from the blood to the survey data in order to determine a correlation between the presence of zoonotic disease, caused by germs that spread between animals and people, and types of interactions. They hope to learn which factors drive some individuals to have more exposure to infectious diseases than others.

Their research is now supported by a $2.5 million NIH grant in the Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Disease program, including supplemental funds awarded this fall.

This summer, the National Science Foundation awarded a $1 million grant to the Triangle Center for Evolutionary Medicine, which Nunn directs. Researchers from the Duke collaboratory as well as UNC and NC State will investigate questions about the early stages of disease outbreaks.

The novel approaches developed for the Madagascar research motivated this latest external grant. The findings will be applicable to a broad range of settings worldwide, including for pandemic prevention.

| Seed funding through the Collaboratories program supports Duke University’s strategic priorities of investing in our faculty and empowering the brightest and boldest thinkers to solve the world’s most pressing challenges. |